The Sacraments of Christian Religious Initiation

The Sacraments of Christian Initiation are the heart of the Catholic faith, since through them the Lord grants his grace, makes himself present and acts in us. The visible rituals through which the sacraments are officiated represent and execute the particular graces of each of them. Find out much more by continuing to read this article.

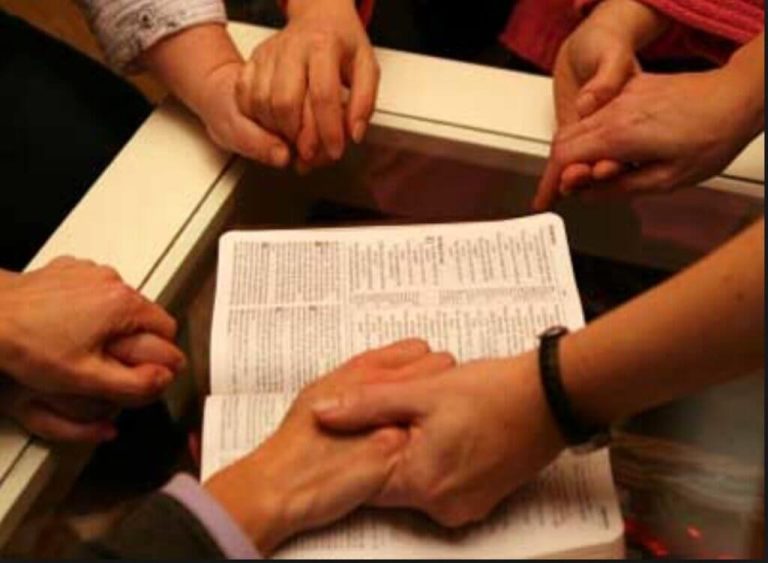

Sacraments of Initiation

According to the doctrine of the Catholic Church, the sacraments are precise and sure signs of divine grace and through which divine life is granted; that is, they confer on the devotee being children of the Lord. The sacraments are given at different moments of the Christian’s existence and in a symbolic way they fully understand it, from baptism to the anointing of those who are sick (prior to the Second Vatican Council it was provided only to those who were in danger of death ).

Most of the sacraments of initiation can only be offered by a priest. Baptism, in exceptional situations, can be conferred by any lay person, or even non-Christian, who has the purpose of doing with the sign what the Church itself does. Added to this, in the sacrament of marriage the ministers are the same contracting couple.

in the new testament

The initial theological word that the Fathers used to denominate in a generic way the Christian rites was that of mysterion. The Latin word sacramentum is a translation of the former (as it also appears in the Vulgate, which almost constantly translates the Greek term by sacramentum).

It seems that the expression comes from the Jewish sphere and not from the Greek (in which it indicated both the divinity and its “enigmas”) and is linked with consideration, recommendation, design towards redemption or the final judgment. In the Gospel it is presented in Mk 4, 11 and its parallel writings: «the enigmas of the Kingdom of God», that is, the divine will that all men be redeemed: this redemption is offered by Christ through his sacrifice in the cross.

In the epistles of Saint Paul the word mysterion appears on some 21 occasions. With it, the enigmatic “saving” plan of God would be pointed out, which has been definitively consummated in Christ, giving rise to the stage considered to be the end of history (since a new manifestation or covenant is not expected) and which is the summary of all things in Christ.

In this way, Christ is included, but also how much he did to redeem men and therefore his mystical entity that is the Church. Based on this, the Catholic Church reinterprets these biblical episodes as that, just as the Gentiles were participating in this redemption and the Church, they were accelerating the definitive fullness of the redemption.

Additionally, it is interpreted that the “mysterion” or sacrament are the signs and miracles that make God’s will come true for all men to be redeemed through the Church, thus realizing the essential sign and miracle: Christ in his Incarnation, Death and Resurrection.

in the patrology

The study of the life and work of orthodox and heterodox writers who wrote about theology from the very beginning of Christianity to the seventh century in the West and the eighth century in the East is called Patrology. In this section his consideration is particularly related to the analysis of the Sacraments.

Greek patology

In the 1st and 2nd centuries

For the authors of the first and second centuries the word mysterion was reserved for the “deed of redemption.” For Saint Ignatius of Antioch, mysterion included the events related to the salvation of Christ’s existence. Saint Justin uses mysterion, in addition, to the characters and prophecies of the Old Testament (and equates Christian ceremonies with the mysteria of mystery beliefs). Saint Irenaeus of Lyon does not use the term to preclude confusion with Gnosticism.

In the III Century (Alexandrian Fathers)

Mysterion is the name given to the hidden connection between image and model that is revealed to the initiate through a teaching (mystagogia). In this way, it was used in Christian rites and salvific events, always keeping in mind the divine determination for the redemption of men and the figures that the ceremony offers to signify them.

Clement of Alexandria uses mysterion to denote cultic rituals, whether pagan or Christian in nature. The wise Origen uses the word with a Platonic meaning, that is, as an emblem or type of the history of redemption insofar as Christ is present in its totality. Origen is attributed a definition of a sign that will be used in sacramental theology by St. Augustine: “a sign is a sensible truth that connects with an invisible truth.”

In the IV and V centuries

Motivated by the decline of paganism, the word mysterion became popular, since there was no longer any possibility of confusion with Gnostic rituals. Saint Athanasius gives the word the meaning of a salvific purpose that took place in the past and is celebrated in the liturgy. Just as Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa and Gregory of Nazianzus highlight divine participation in the world, which is also an exaltation of mundane reality.

In this way, the mysterion of the plan of redemption is divided into the three primordial events of that exaltation: the Incarnation, Pentecost and the Eucharist. John Chrysostom frequently uses the term “mysterion” to refer to Christian rites. Cyril of Jerusalem associates it with God’s act of redemption through Christ that is commemorated in the liturgy.

In such a way that his mystagogic catechisms are an incorporation of the devotee to the experience of the most important rituals: Baptism, Anointing and the Eucharist. With Pseudo Dionysius the Areopagite, such an affinity of mysteria with the proper rituals of the Church becomes methodical. Firstly, he describes mysterion as the ritual acts that through the invocation of the Church to the Holy Spirit, the redeeming grace of God, operate on people or things. He then differentiates three aspects of mysteria:

- Consecration Acts: (Baptism, Communion and Anointing).

- Those who consecrate: bishop, priest and deacon.

- To whom it is consecrated: inferiors, purified, therapists or monks.

Latin Patrology

In the third century

In North Africa, the translation “sacramentum” became popular for the term mysterion, although the Latinized word “mysterium” was also used. Tertullian, based on the legal conception that the expression “sacramentum” held in Roman culture (an oath of loyalty of a religious nature), applied it to Baptism, since, according to his criteria, in Baptism a pact is made between the Lord and the baptized.

But also together with the Greek idea of mysterion, applying it to the other Christian rituals. Cipriano de Cartago admitted these meanings, granting them an ecclesial scope by incorporating the link between the baptized and the bishop.

In the IV-V Centuries

At this stage, the term “sacramentum” was used with the same meaning as mysterion associated with the acts of worship of the Church. Ambrose of Milan expanded the scope of the term with reflections that got little echo in his contemporaries: he understood sacramentum as the events of the history of redemption and encounter with Jesus Christ.

Augustine of Hippo uses the word sacramentum to indicate the rituals of both the chosen people and the Church. He also uses it to indicate the figures or signs of Christ in the Old Testament and finally to refer to the “storehouse of faith.” He likewise uses the word mysterium to point to the concealed, the hidden according to the ancient Greek meaning.

However, he will expose a vast doctrine of the sign of something sacred although with great influence of his Platonic philosophy: his thought will be used later in sacramental theology. He accepts that these sacred signs must have a material element and an expression that completes them and that enables the application of the notion of memorial of the Hebrew cult. Thus, he later offers a description in his letter to Januario (letter 55) in which he links the sacrament with a celebration.

Who guarantees the effectiveness of these sacraments, according to Augustine, is Christ himself through the ministers of worship. Augustine’s controversy with the Donatists will give him the opportunity to establish a new distinction by which the value of a sacrament is divided by its efficacy (the baptism of the Donatists would be legitimate but would not grant the grace of faith).

In theology, later the valid external component will be called “signum” (sign) and “res” the associated grace. Later writers (Leo I the Great, Gregory the Great) treated mysterium and sacramentum as synonyms, giving them the general scope they held in Greek theology.

in the scholastic

Through the first Middle Ages and after the Germanic occupations, the Neoplatonic philosophy that was the foundation of the Fathers’ reflection lost influence. The idea of mysterion began to be applied only to the unveiled truth that requires a conformity of faith. The word sacrament remained to indicate a specific sign by which God proceeds .

Just as the idea of sign was losing ontological solidity to move to the level of mere reference, problems arose for the proper understanding of the dogma about the genuine presence of Christ in the Eucharist. In such a way that a deeper reflection on the notion of sacrament was required that would make it possible to properly establish its virtuality.

Berengar of Tours owes a definition that was very successful a posteriori: «Visible form of a grace that cannot be seen», in which the term form indicates only the allusion but not the real presence. Hugh of St. Victor is the one who first wrote an essay about the sacraments: De sacramentis christianae fidei, in which he gives his own description of it where he still takes into account the whole story of redemption but narrows the scope.

She applies this conception of the sacrament not only to the contemporary sacraments of the Catholic Church but also to those she calls “sacramentals.”

Just as the sacraments are taking shape as rituals, reflection begins, hand in hand with the growing influence of Aristotelian philosophy, on the fundamentals of the ceremony or what is inevitable for the sacrament to be legitimate. The idea of cause and the difference of matter and form notably promoted reflection on the sacraments.

Through the idea of cause, Pedro Lombardo reincorporated the effectiveness of the sacrament, which will come to be “the cause of the grace of which it is the image”. In this way, the number of seven could be established (although some point out that it was rather due to a choice of convenience). Hugo de San Caro incorporated the matter and form difference in the sacrament based on the description of Agustín de Hipona.

Thomas Aquinas extensively considered the sacraments in his treatises. He admits the previous reflection about the sacrament as a remedy for sin, but improves it with the meaning of an act of worship (equally present in the previous writers) and in the third section of the Summa Theologica, in the treatise that he offers them, he poses them as communication and application of the redemption of Christ for the sanctification of men.

In this way, it takes the elements of the previous reflection and improves them with the Aristotelian philosophy. He poses it this way, yes as a sign but equally as a cause and, therefore, recovers its supernatural effectiveness. And he places the effective cause on three levels: that of God who causes grace, that of the humanity of Christ who obtained redemption, and that of the minister by the sacrament itself.

Regarding the application of the matter and form difference, it highlights the highest value of the form (words) and values ”matter” not the components but the actions. For Thomas Aquinas, the effectiveness of the sacrament is largely due to faith, although to a lesser degree in those sacraments where there is propensity of the person who obtains it for acts of worship. Such propensity is what Thomas calls “sacramental nature.”

The number of sacraments, proposes seven based on an anthropological reflection associated with human circumstances: birth, development, nutrition, suffering, vitality first, diffusion, government. This appreciation with certain variants has been admitted by the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

During the Second Council of Lyon, a confession of faith was read that ensures “septem ecclesiastica sacramenta”. The subsequent period is that of the controversies between the Franciscan and Dominican schools on the problem of the causality of the sacrament.

The Council of Trent and the Post-Tridentine Era

The central issue in the dispute with the Protestants was that of the excuse. For this reason, the thought of those who participated in the Council of Trent was oriented there, although they did not have the intention of producing systematic treatises on the issues discussed.

Reform

In a generic way, the doctrine of the Reformation denies the effectiveness of the sacrament in relation to grace, since it considers it only a human action that cannot make it obey divine action. This based on the textual reading of the Bible, which shows no sign of the existence of such sacraments granted in that particular way.

Luther assures that the sacraments are resources to increase faith, that faith that makes us believers in those who have achieved redemption for us. The sign, whatever it may be, is insufficient to replace the Christian’s faith and ultimately proves fruitless in itself. This idea of a sacrament made it possible to reduce its number to two, called ordinances by the evangelicals: Baptism and Communion or Santa Cena.

John Calvin, who holds as his foundation his theory about predestination and the apathy of the act of faith, grants the sacraments the merit of external testimony or evidence of God’s action in the soul.

ordinances

Protestants and Evangelicals see the ordinances as symbolic manifestations of the gospel announcement that Christ existed, perished, was raised from the dead, rose to heaven, and will return one day. Rather than requirements for redemption, the ordinances are visual aids to better understand and appreciate what Jesus Christ accomplished for us in his saving work.

The ordinances are defined by three elements: they were established by Christ, the apostles were instructed, and they were put into practice by the early church. Since baptism and communion are the only rituals that are conceptualized under these three elements, there can be only two ordinances, neither of which are requirements for redemption.

The Council of Trent

The Council of Trent consecrated its seventh session to consider the matter of the sacraments. Although he did not offer a formal description of the sacrament, he established the now traditional declaration of Berengar of Tours: «visible form of grace that cannot be seen», additionally using the category of the symbol that contains and grants the grace that it signifies. In addition to this, the number of seven sacraments was fixed.

Likewise, and despite the controversies between theologians and bishops, the affirmation by which the sacraments would have been established by Jesus Christ was admitted (despite the fact that the present schools described the idea of ”establishment” in various ways). From this, the common origin and the impossibility of changing its substance does not mean, always according to the council fathers, that all the sacraments are identical in dignity.

Contrary to Reformation theology, the Council ensured the effectiveness of the sacraments as long as the recipient does not place impediments to grace. It is true that to avoid conflicts with the orthodox, the expression “include grace” was used and not “cause grace” and include it “ex opere operato”, according to the expression that indicates its own supernatural effectiveness.

However, such effectiveness was subject to the minister wanting to achieve with them what the Church does and do the basics of each sacrament. Additionally, it was pointed out that there were three sacraments that conferred “character” (and that, therefore, could be obtained only once): Baptism, Confirmation and Holy Orders.

The Counter Reformation

The main issues faced by Counter-Reformation theologians are: the description of sacraments, the manner of causing grace in them, and the character of sacramental grace (in connection with sanctifying grace).

Pius V’s Catechism provided a definition that incorporated the various elements of Trent, and Pope Alexander VII made it clear that when the Council indicated that the minister should claim to do what the Church does, such claim is not only external (performing in detail the prescribed rite) but equally internal (wanting to do with it what the Church says is done).

Illustration

The emergence of rationalism meant a break in the theology of the reformers who were marginalizing symbolism. The response of the Catholics was rather to highlight the impartiality of the act of faith but also, in certain cases, that of such a demand for sufficiency that the sacramental practice was considerably reduced.

In Contemporary Catholic Theology

The Second Vatican Council

What was reflected by the Second Vatican Council would be influenced by the liturgical and patristic movements. Thanks to these theological trends, it was possible to recover the idea of mysterion that had been applied to the Church and that played an outstanding role in conciliar controversies. Another contemporary theological advance that shed light on the idea of sacrament was the theology of history.

By highlighting the fundamental historical feature of Christianity, the sacraments are seen as “acts of redemption”, comparable to the events that the Old Testament recounts in the life of the people of Israel. In this way, the theologian Jean Daniélou collects, based on the mystagogy of Greek patrology, the notion of the place of the sacraments for the final restoration of all things in Christ (eschatology): memorials of the Christian Easter.

The council fathers collected and admitted these theological considerations in the Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium and in the Dogmatic Constitution Lumen Gentium. Additionally, Trent’s ideology regarding faith was improved: The sacraments “fidem non solum supponunt, sed verbis et rebus alunt, roborant, exprimunt; quare fidei sacramenta dicuntur” (SC 59).

There have been three reflection considerations that post-conciliar theology has pursued:

- Delve into how each sacrament is an approach to Christ.

- It takes up the centrality of the Eucharist, drawing the pertinent conclusions.

- Linking the sacraments with the sacramentality of the Church.

In the Catechism of the Catholic Church

As previously alluded to, this writing accepted the anthropological explanation regarding the quantity of the sacraments. Thus, in relation to the explanation, it admits and finishes off the theology of the Second Vatican Council.

Numbers 1113 to 1130 speak of the relationship between the Paschal Mystery and the sacraments. From the numerals 1135 to 1186 he frames them in the liturgy of the Church. Finally he devotes section number two of the second part to the seven sacraments.

In numeral 1084, after recalling that the sacraments were created by Christ, he provides a definition: «The sacraments are sensible signs (words and actions) accessible to our humanity today. They effectively execute the grace they suppose by virtue of the action of Christ and by the power of the Holy Spirit».

Or likewise in numeral 1131: «The sacraments are effective signs of grace, conferred by Christ and entrusted to the Church through which divine life is granted to us. The visible rituals by which the sacraments are commemorated represent and perform the particular graces of each sacrament. They are profitable for those who receive them with the required conditions.

Catholic Theology: The Seven Sacraments

What are the Sacraments of Initiation ? The Catholic Church officiates seven, and they are called: Baptism, Confirmation (or Chrism), Eucharist, Reconciliation (or Penance), Anointing of the Sick, Holy Orders, and Matrimony. According to his doctrine, “all the sacraments are established for the Eucharist “as for their purpose” (St. Thomas Aquinas)”. In the Eucharist, the renewal of Christ’s paschal mystery is achieved, thus replacing and updating the redemption of humanity.

The Catholic sacrament is a ritual event dedicated to the devotees, so that they obtain divine grace, and also dedicated to granting sacredness to certain moments and situations of Christian existence. They were established by Jesus Christ as “perceptible and effective signs of grace […] through which divine life or redemption is granted to us” and were entrusted to the Church.

By means of these divine signs or gestures, “Christ operates and transmits grace, independently of the personal holiness of the minister”, although “the benefit of the sacraments also depends on the conditions of the one who receives them”.

By officiating them, the Catholic Church, through words and ceremonial elements, nurtures, manifests and fortifies her faith and the faith of each of her devotees. These signs of grace make up a component and inalienable part of the Christian existence of every believer. The sacraments are indispensable for the redemption of believers since they grant divine grace, “the absolution of sins, the adoption of children of the Lord, conformation to Christ the Lord and being part of the Church”.

The Holy Spirit prepares for the reception of the sacraments through the Word of God and the faith that admits the Word in hearts that are ready. Thus, the sacraments strengthen and manifest faith. The benefit of sacramental existence is simultaneously personal and ecclesial. On the one hand, this benefit is for each devotee a life for God in Jesus; on the other hand, it is for the Church her constant increase in charity and in her task of witnessing.

The sacraments become divine gestures in the existence of each believer, manifesting themselves in a symbolic and spiritual way; therefore, they are considered:

- Sacred signs, since they manifest a sacred, spiritual truth;

- Effective signals, since, in addition to representing a certain effect, they actually generate it;

- Signs of grace, since they transmit various gifts of God’s grace;

- Signs of faith, not only because they suspect the faith of those who obtain them, but also because they feed, strengthen and manifest their faith.

The Seven Sacraments of Initiation

The seven sacraments define the different phases of importance in the Christian life of the faithful, which are separated into three categories:

- Sacraments of Christian Initiation (Baptism, Confirmation and Eucharist) that “establish the foundations of Christian existence: believers reborn in Baptism, strengthened by Confirmation and nourished by the Eucharist”;

- Sacraments of Healing (Penance and Anointing of those who suffer from illness);

- Sacraments to serve communion and mission (Order and Matrimony).

These sacraments can also be grouped into just two categories:

- That they manifest a permanent nature and leave an indelible mark on whoever obtains them, and therefore can only be supplied once to each believer. They are Baptism, Confirmation, Marriage and Orders;

- Those that can be supplied repeatedly.

Baptism

Baptism is understood as the sacrament to open the doors of Christian existence to the baptized, integrating him into the Catholic community, into the great Mystical Body of Christ, which is the Church itself. This ritual of Christian initiation is regularly performed with water in the act of baptism, by being immersed in it or being poured or sprinkled.

Using other words from the Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, «in the fundamental ritual of Baptism it is a matter of immersing the aspirant in water or sprinkling the water on his head, while calling out the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit”. Baptism means immersion “in the death of Christ and risen with Him as a new being”.

Baptism absolves the initial sin and all one’s own sins and the punishment resulting from sin. It allows the baptized to be part of the Trinitarian existence of God through sanctifying grace and integration in Christ and in the Church. It also grants the theological virtues and the gifts of the Holy Spirit. Every time he receives baptism, the Christian is eternally a child of God and an inalienable member of the Church, he is also a part of Christ forever.

In addition to this, the baptized person participates with Him in the task of being a Prophet, a Religious or in that of being a King. In the first, he is in charge of lecturing the divine word, especially to children or those who do not know Jesus, in the second, he dedicates himself to offering sacrifices to God in our daily lives, stopping carrying out activities that are to our liking or doing the that we do not like, always offering them for some personal purpose, keeping in mind that everything is for greater divine glory.

In the third task, that of being a Monarch, one must be interested, just like Jesus, in the most needy and marginalized: poor, suffering, in prison, taking care of praying for them if we cannot provide them with physical help.

Although baptism is essential for redemption, the catechumens, “all those who perish for faith (Baptism of Blood), […] all those who, under the stimulus of grace, who do not know Christ and the Church sincerely seek God and insist on fulfilling his will (Baptism of Desire)”, manage to achieve salvation without being baptized, since, according to the doctrine of the Catholic Church, “Christ perished for the salvation of all.”

For children who die without being baptized, the Church points out in its liturgy “to trust them for the mercy of God”, which is inexhaustible and infinite.

Institution

Numerous early representations of this sacrament appear in the Holy Scriptures. This is remembered at the Easter Vigil when the baptismal water is blessed. Genesis tells us about water as the principle of life and fertility. Sacred Scripture tells us that the Spirit of God “rose” over her. ( Gen. 1,2 ).

Noah’s ark is another of those representations that the Church alludes to us. Because of the ark, “a few, that is, eight persons, were redeemed by means of water.” (1 Pet. 3, 20). If spring water symbolizes life, the water in the sea is a sign of death. Therefore, it could be a sign of the enigma of the cross. By this symbolism, baptism means “communion with the passing of Christ.” (Catech. no. 1220).

Particularly the passage of the Red Sea, genuine liberation of Israel from the yoke of Egypt, is in which the freedom worked by baptism is announced, they enter the water as slaves and emerge liberated. Likewise, the passage through the Jordan, in which the people of Israel obtains the promised land, is a prefiguration of this sacrament. (Cf. Catech. 1217-1222).

All these anticipated representations culminate in the figure of Christ. He himself obtains the baptism of John, the Baptist, which was intended for sinners and without having committed any fault, he offers himself to “fulfill all justice” (Mt. 3:15). He lowers the Spirit on Christ and the Father declares Jesus as his “beloved Son”. (Mt. 3, 16-17). Christ baptized her out of love and humility, and thus serve as an example.

If we remember the meeting of Jesus with Nicodemus, we contemplate how He shows him the need to obtain baptism. (Cf. Jn. 3, 3-5). After the Resurrection he grants the mission of baptism to his apostles. “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me; go therefore, teach all nations, giving them baptism in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.” (Mt. 28, 18-19).

With his Passover, Christ made baptism possible for every man. He had already recounted his passion, “baptism” with which he was to be baptized (Mk. 10,38) (Lk. 12,50). The blood and water that emerged from the side pierced by the lance of the soldier of Jesus crucified (Jn. 19,34), are images of “baptism” and the “eucharist”, the two sacraments of new life (1 Jn. 5, 6-8); since then it is possible to be “born of water and of the Spirit” to enter the Kingdom of God. (Jn 3,5).

Beginning on the day of Pentecost, the Church has provided baptism by following in the footsteps of Christ. Saint Peter, on that date, calls for conversion and baptism to obtain absolution of sins. The Council of Trent proclaimed as an affirmation of faith that the sacrament of Baptism was established by Christ.

Age

For the Catholic Church, baptism is granted both to children and to adults who have been converted and who have not previously been legitimately baptized (baptism, in most Christian Churches, is considered lawful by the Catholic Church since it is considered that the effect proceeds directly from God, irrespective of personal faith, though not of the priest’s purpose).

Even so, the Catholic Church has insisted on baptism for children since “having come into the world with original sin, they need to be freed from the power of the wicked and be led to the free kingdom of the children of God.” For this reason, the Church advises believers to do all they can to prevent an unbaptized person from coming to perish in their presence without the favor of baptism.

In this way, despite the fact that the sacrament must be administered by a priest, before a sick person without baptism any person has the power to do so, so they must baptize him, indicating: «I baptize you in the name of the Father, of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” to the extent that, with the thumb of his right hand, he traces a cross on the patient’s forehead, mouth and chest.

The Bible recommends that Baptism should be administered to those who have a complete understanding of good and evil, it must be carried out by complete immersion, simulating the death and burial of Christ. The intention is to make their faith known, even though we harbor the inheritance of sin, and come into the world in sin, we are definitely not sinners.

The circumstance that baptism is usually given to newborn children, who, therefore, not entering Christian existence of their own free will, shows that there are other things that are required by these people to obtain another sacrament, Confirmation. . This is reached when they reach an age where they have enough reason and intelligence to consciously practice their faith and then determine whether or not they should stay in the Catholic Church.

If so, then you will find yourself in this case, confirming the resolution that your parents or guardians took on your behalf on the date of your baptism. However, as this sacrament instills character, whoever obtained baptism, regardless of whether or not he validates it through the sacrament of Chrism or Confirmation, will be baptized for eternity.

symbols

Within the Catholic Church, the sacrament of baptism has various symbols, but there are four main ones, which are: water, oil, the white mantle and the candle. Each one symbolizes an enigma in the life of the baptized. In addition to these symbols (which are the most important), the Roman ritual also includes salt, but this symbol is only used according to the pastoral guidelines of the particular Churches.

Below is the meaning of the symbols:

- Water : Symbolizes the passage from the “pagan” existence to a “new life”. She has the element of purification, by washing away original sin.

- Oil : Symbolizes the strength of the Holy Spirit. In ancient times, wrestlers used the oil prior to the fight to strengthen their muscles and thus be able to win. In the new existence achieved through baptism he contemplates the same function, covering the baptized for the daily struggles against the challenges of the evil one.

- White Mantle: Symbolizes the new life achieved by baptism. After taking a bath we put on clean clothes, at baptism it would be no different. We are purified in the water and clothed with a new life.

- Candle : It has two meanings: the Holy Spirit and the gift of faith. Through baptism we are covered with numerous graces and the primary one is the Holy Spirit, since we will be united to God as children to be consecrated and this sanctification is carried out through the Holy Spirit. Faith is an essential gift for our existence, it is through which we recognize God and through it we obtain grace from him.

The Celebration of Baptism

Who can be worthy of Baptism and who can provide it? That human being who has not received baptism, and only he, has the power to receive it. The regular minister of Baptism is the one who provides it, whether he is a bishop or a presbyter and, in the Latin Church, likewise the deacon. If necessary, it can be any person, even non-baptized, if he is willing to do it according to what the Church does when baptizing and uses the Trinitarian baptismal formula.

Celebration

Christian Baptism is officiated by bathing the recipient in water (act of immersion) or by pouring water on the head (act of infusion), while the minister cries out to the Holy Trinity. The complete ritual is composed of three moments.

Preparation: It is about the blessing of the water, in the resignation of the parents and godparents to sin, in the exercise of faith and in a question to the parents and godparents about whether they want the child to receive baptism.

Ablution or Baptism: As the minister bathes the person who is baptized with water, he exclaims: “I granted you baptism in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit”

Complementary rites: They are composed of the chrismation, the white mantle and the delivery of light. Chrismation is the process by which the minister anoints the head of each baptized person with the sacred chrism, as a sign of admission as part of the devout people; The white mantle, sign of the new life and pride of the Christian. The delivery of the light of Christ manifested by a candle whose flame is taken from the Paschal candle.

Chrism or Confirmation

Confirmation of Baptism or Chrism is called the act when the one who received baptism confirms his faith in Christ, receiving the anointing through the ceremony as well as the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit. The anointing is imparted by the Bishop or father with authorization and consecrated oil is used for it on Holy Thursday.

It is a sacrament that is considered among the sacraments for the Christian beginning by which those who received baptism are fully incorporated as members of the community. For those who have received baptism, the sacrament of Confirmation binds them more intimately to the Church and benefits them with a particular strength of the Holy Spirit.

In a simple way, the act is the renewal of the “baptismal promises”, questions made by the bishop who directs them, which he says aloud and answers in the same way in the Confirmation of the community. As in baptism, confirmation also instills character, and can only be given once to each person.

Since it is an act of assent to the commitments, the person may never obtain the chrism or, even if he participates in the ceremony, he does not end up confirming these commitments. In any case, the one who did not obtain confirmation or who did not want to renew the commitments of baptism, he can obtain them at any time. Chrism is therefore a subordinate sacrament, which complements baptism, since it has no relevance given to those who have not received baptism.

Institution

The Council of Trent proclaimed that Confirmation was a sacrament established by Christ, despite having been rejected by the Protestants because, according to them, the exact moment of its establishment was not known. It is known that it was established by Christ, since only God can combine grace with an external sign.

Additionally we find in the Old Testament, many allusions by the prophets, of the work of the Spirit in the messianic era and the same warning of Christ of an arrival of the Holy Spirit to consummate his work. These notices point us to a different sacrament than Baptism.

The New Testament tells us how the apostles, in obedience to the will of Christ, laid on their hands, transmitting the Gift of the Holy Spirit, dedicated to supplementing the grace of Baptism.

“When the apostles who were in Jerusalem learned that Samaria had admitted the Divine Word, they sent Peter and John to them. They descended and prayed for them to receive the Holy Spirit; for he had not yet descended upon any of them; they had only been baptized in the name of the Lord Jesus. It was thus that they laid their hands on them and welcomed the Holy Spirit.” (Acts 8, 15-17; 19, 5-6).

Meaning of Confirmation

The Second Vatican Council states: “Through the sacrament of Confirmation they associate (Christians) more closely with the Church, they benefit from a special energy of the Holy Spirit and thus are forced more rigorously to spread and defend the faith. as authentic witnesses of Christ, by word in conjunction with deed” (Lumen Gentium, 11)

First of all, it is convenient to reaffirm that the sacrament by which we obtain the Holy Spirit, the Sacrament of the Spirit, is Baptism. With it we are born in a spiritual way and we become part of the existence of the Holy Trinity and we begin to live a superhuman existence. Confirmation is the strengthening of Baptismal Grace.

It is a spiritual progress since in this sacrament the promises of Baptism that others made for us are renewed if it was received shortly after birth. Its purpose is to improve what Baptism started in us. It can be pointed out that in a certain way we are baptized in order to be confirmed later.

The most characteristic of the sign of Confirmation is the laying on of hands and the anointing with chrism. With this process, the name of Christian is made known, which means “anointed” and that originates in the name of Christ, whom the Lord anointed with the Holy Spirit.

Who Can Receive this Sacrament?

Anyone who has received baptism can obtain the sacrament of Confirmation. Even so, it is suggested that it be obtained by having full use of reason, since this sacrament is estimated as “the sacrament of one who is Christianly mature.” Advance preparation is required so that the confirmed person can better undertake the apostolic obligations of Christian existence.

As previously explained, the particular grace of this sacrament is the strengthening of faith, the increase of sanctifying grace. The Lord cannot increase what is not present, hence the one who obtains it must do it in a situation of Grace, this is to repent and manifest the sins prior to confirmation. To obtain it in mortal sin would be to abuse the sacrament, a grave lack of sacrilege.

The regular minister of Confirmation is the bishop, although, if necessary, he can confer the power to administer the sacrament to priests, it is convenient that he grant it himself, without forgetting that for this reason the office of Confirmation was provisionally separated from Baptism.

The bishops are the heirs of the apostles and have obtained the entire sacrament of Holy Orders. For this reason, the provision of this sacrament by themselves shows that Confirmation has the fruit of uniting those who obtain it more closely with the Church, their apostolic origin and their purpose of bearing witness to Christ. (CCC, 1290)

Confirmation Celebration

In the liturgical office of this sacrament three elements converge that must be indicated:

- The regeneration of the promises of Baptism, by which the person confirming makes a sincere manifestation and commitment to live in the manner of Christ.

- The imposition of hands that the bishop performs on the confirmands. The decisive moment of Confirmation by which the Bishop places his hand on the head of the confirmand and anoints his forehead with the sacred Chrism while exclaiming these words: “obtain by this sign the gift of the Holy Spirit”

The greeting of peace ends the ritual, denotes and expresses the ecclesial communion with the bishop and with all believers.

Eucharist (First Communion)

The endless richness of this sacrament is manifested in the different names that have been given to it:

Eucharist : of Greek origin “Eukharistia”, means “thanksgiving”. This word recalls the Jewish blessings that acclaim the works of God: creation, salvation, sanctification. (cf. Lc. 22,19; 1 Cor 11,24; Mt 26,26; Mk 14,22).

Banquet of the Lord: since it is the Supper that the Lord officiated with his proselytes on the eve of his passion (1 Co 11,20).

Fraction of the Bread: since this rite was used by Jesus when he blessed and distributed the bread as head of the family. With this term the first Christians called their eucharistic assemblies. With these words it is meant that all those who feed on this only broken bread, which is Christ, enter into communion with Him and form a single body in Him (cfr. Mt 14,19; 15,36; Mk 8, 6 -19; Acts 2,42.46; 20, 7.11; 1 Co 10, 16-17).

Eucharistic Assembly : since the Eucharist is officiated in the assembly of the devotees, a visible manifestation of the Church. (Cf 1 Cor 11, 17-3)

Holy Sacrifice : since it updates the only sacrifice of Christ the Redeemer and incorporates the offering of the Church (Cf. Acts 13,15; Ps 116, 13.17; 1 Pe 2,5)

Communion : since by this sacrament we join Christ who makes us part of his Body and Blood to constitute a single body (Cf. 1 Cor 16-17).

Holy Mass : since when the Eucharist is officiated in Latin, people are said goodbye with the phrase “Ite Missa est”, which recounts the sending to comply with the divine will in their lives.

The Holy Eucharist concludes the Christian beginning. Those who have been exalted to be worthy of the true priesthood by Baptism and more intensely conformed to Christ in Confirmation, take part, through the Eucharist with the whole collective, in the very sacrifice of the Lord.

At the Last Supper, Christ established the Eucharistic offering of his body and blood to eternalize the sacrifice of the cross for centuries and entrust the memorial of his death and resurrection to the Church. It is a sign of unity, a bond of love, a Passover banquet in which Christ is received .

It is the commemoration in memory of Christ, celebrating his Last Supper, his passion and his resurrection. In this office, the Christian obtains the consecrated Host. It is the transcendental sacrament, which gives believers the opportunity to obtain and physically ingest what is considered to be the Body of Jesus Christ, into which the bread consecrated by the priest became, just as the wine becomes his Blood.

In the sacrament of the Eucharist, the blessed Host (bread) is distributed to believers, who place it in their mouths and swallow slowly and respectfully. In order to obtain the Host or receive communion, the believer must be in a “state of grace”, that is, they must have previously confessed their sins and obtained divine absolution in the sacrament of Confession or Penance (communion can be taken if the sins are not are serious or fatal offenses).

Regularly, the consecration occurs in the office of the Mass, a ritual also called the Holy Sacrifice. Sacrifice is precisely the act of consecration. It is about the recreation, through the mass, of an episode of the Last Supper of the apostles with Christ, when bread and wine were served to the apostles from Him, notifying them that this was His body and blood.

The Catholic Church maintains that, when the priest pronounces the ritual words “This is my body” when referring to bread and “This is my blood” when referring to wine, a phenomenon called transubstantiation occurs, that is, the material substance that makes up the bread is transformed into the body of Christ and that which makes up the wine is transformed into his blood.

In the Bible, what the Lord Jesus Christ points out is of a figurative nature, like most of his words if an equation or parable is made to understand them better, which is not the case since he only pronounced them to his proselytes and emphasized in the words “this is my body…” and “this is my blood…”.

The bread product of the transubstantiation is distributed to the devotees who, to those who swallow the Host, are swallowing the body of Christ. The Eucharist is considered the sacrament of thanksgiving, in the meaning of the original Greek word εὐχαριστία (transc. “eukharistia”).

Institution

Various anticipated representations of this sacrament have been found in the Old Testament, such as the following:

- The manna, with which the people of Israel were fed through their pilgrimage through the desert. (Cf. Ex. 16,) .

- The offering of Mechizedek, a cleric who, in thanksgiving for Abraham’s triumph, offers bread and wine. (Cf. Gen. 14, 18).

- The same sacrifice of Abraham, who is willing to offer the life of his son Isaac. (Cf. Gen. 22, 10).

- Likewise, the sacrifice of the Passover lamb, which freed the people of Israel from perishing in Egypt. (Cf. Ex. 12).

The Eucharist was also alluded to, by way of prophecy, in the Old Testament by Solomon in the volume of Proverbs, in which he commands the servants to go eat and drink the wine that he had arranged for them. (Cf. Prov. 9,1). The prophet Zechariah mentions the wheat of the elect and the wine that he purifies.

Christ himself, after the multiplication of the loaves, foreshadows his real, corporeal and substantial presence in Capernaum, when he says: “I am the bread of life…. One who eats this bread will live eternally, since the bread that I I will bestow is my flesh, for the life of the world.” (Jn. 6, 32-34;51)

Christ, knowing that his “hour” had arrived, after cleaning the feet of his apostles and granting them the commandment of love, establishes this sacrament on Holy Thursday, at the Last Supper (Mt. 26, 26 -28; Mc. 14, 22 -25; Lk 22, 19 – 20). All this with the purpose of remaining among men, of never separating from his own and making them part of his Passion. The sacrament of the Eucharist emerges from the boundless love of Jesus Christ for man.

The Council of Trent proclaimed as a truth of faith that the Eucharist is an authentic and proper sacrament since in it the fundamental elements of the sacraments are evident: the external sign; substance (bread and wine) and form; grant grace; and was established by Christ.

Christ abandons the order to celebrate the Sacrament of the Eucharist and persists, as can be seen in the Gospel, in the need to obtain it. He points out that you have to eat and drink his blood in order to redeem them. (John 6, 54).

The Church has always been loyal to the mandate of Our Lord. The original Christians congregated in the synagogues, in which they read some Readings from the Old Testament and then what they called “breaking of the bread” took place. Being expelled from the synagogues, they continued to meet in a certain place once a week to distribute bread, thus fulfilling the order that Christ left to the Apostles.

Gradually new readings, prayers, etc. were added to it. until in 1570 Saint Pius V defined how the rite of the Mass should be, which was maintained until the Second Vatican Council.

the communion

The Lord communicates to us an urgent invitation to be received in the sacrament of the Eucharist «In truth, truly I say to you: if you do not eat the flesh of the Son of man and drink his blood, you will not have life in you» (Jn 6, 53).

To answer this invitation, we have to get ready for this great and holy moment. Saint Paul encourages an examination of conscience: “Whoever feeds on the bread or drinks from the chalice of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be a prisoner of the Body and Blood of the Lord. Evaluate yourselves, then, all of you, and then feed on the bread and drink from the chalice.

Since whoever eats and drinks without distinguishing the body, eats and drinks his own pain» (1 Cor 11, 27-29) Whoever is aware of being in severe sin must obtain the sacrament of Reconciliation before approaching Communion.

Given the grandeur of this sacrament, the believer can only reiterate with humility and with passionate faith the words of the Centurion “Lord, I am unworthy of you entering my house, but a word from you will be enough to heal me”.

The Church forces believers to take part on Sundays and feast days in the sacred liturgy and to welcome the Eucharist at least annually, if feasible in the Easter season. But the Church strongly encourages devotees to welcome the Holy Eucharist on Sundays and holidays, or even more frequently, even daily.

fruits of communion

- It increases the alliance with Christ: «who feeds on my Flesh and takes my Blood, lives in me and I in him» (Jn 6,56.

- Strengthens the Spirit: What is produced by material food in corporeal life, communion does admirably in spiritual existence. Communion preserves, increases and renews the life of grace obtained in Baptism.

- Away from sin : as food is useful to replenish the loss of strength, the Eucharist strengthens compassion, which in daily life tends to be weak, and this reanimated compassion eliminates venial sins. The more you participate in the life of Christ and the more you advance in his friendship, the more difficult it is to break with him for mortal sin.

- It implies a commitment in favor of others: to truly obtain the body and blood of Christ to whom we give ourselves, we must recognize Christ in our neighbor, particularly in the most humble and needy.

- Strengthens the unity of the Mystical Body: The Church is made by the Eucharist. Those who obtain the Eucharist are joined more closely to Christ, for this very reason, Christ brings together all believers in a single body that is the church. Communion renews, strengthens and deepens the integration into the Church already made by Baptism.

The Eucharistic Celebration

The Eucharist or Mass is made up of two great components. On the one hand, the Liturgy of the Word, which is divided into:

- Entrance rite: Christians attend the same place for the Eucharistic assembly praising and giving thanks to the Lord. In front is Christ himself who is the Supreme Priest, his delegate is the priest who directs the office and operates on his behalf. It begins with the greeting crying out to the Holy Trinity

- Penitential act: it is to accept sinners and ask God for absolution to prepare to hear his Word and commemorate the Eucharist with dignity conformed in a community. It includes the Lord Be Pious and the Glory Be, in addition to the Opening Prayer that generally manifests the nature of the office with a prayer to God the Father, through Christ in the Holy Spirit.

- Liturgy of the Word: it is made up of the readings from Sacred Scripture, followed by the homily, which is a reflection and description of the Divine Word. The Creed or Profession of Faith is recited and the Prayer of Believers is performed.

On the other hand is the Liturgy of the Eucharist, which is divided into:

- Offertory : or exhibition of the offerings that are placed on the altar, made up of bread and wine that, together with the life of man, are offered to God.

- Eucharistic Prayer : God is thanked for the work of redemption and for his gifts, bread and wine. The presence of the Holy Spirit is requested to transform them into the Body and Blood of Christ, reiterating the same words that Jesus spoke at the Last Supper.

- Fraction of the Bread and the Communion Rite: which expresses the unity of believers. The Our Father is recited and the devotees obtain the Body and Blood of the Lord, just as the Apostles obtained them from the hands of Jesus.

- Farewell rite: Greetings and blessing from the priest, to end the farewell in which the people are summoned to return to their activities, bringing the Gospel to life.

Therefore, we must consider the Eucharist as:

- Thanksgiving and Praise to the Father

- Memorial of the Offering of Christ and his Body

- Appearance of Christ by power of his Father and his Spirit

«Jesus hides himself in the Blessed Sacrament of the altar, so that we dare to treat him, to be our sustenance, so that we become one with him. By pronouncing that without me you can do nothing, he did not condemn the Christian to inaction, nor did it force him into an intricate and hard search for his Person. He has remained among us always available ».

When we congregate in front of the altar while the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass is officiated, when we observe the Sacred Host exhibited in the monstrance or venerate it hidden in the Tabernacle, we must revitalize our faith, reflect on that new existence, which comes to us, and move us before the affection and divine tenderness» (J. Escrivá de Balaguer, It is Christ who passes by No. 153).

The Church knows that, already at this moment, the Lord arrives in his Eucharist and that he is there among us. However, this appearance is hidden. That is why we officiate the Eucharist “while we await the glorious arrival of Our Lord Jesus Christ”

Confession or Reconciliation or Penance

Given that the new existence of grace, obtained in Baptism, did not eliminate the vulnerability of human nature or the propensity to sin (concupiscence), Christ established this sacrament for the transformation of the baptized who have separated from Him for the sin.

It is the revelation of sins to a priest, who imputes penance so that, once consummated, reconciliation with Christ is propitiated. That is to say, it is the sacrament that gives the Catholic Christian the opportunity to accept his sins, repent and try not to sin anymore, in order to be absolved by God.

Recognizing sins lies in their confession to a priest, who hears them in the name of God and grants that devotee absolution and peace through the ministry of the Church. From the formal perspective, the one who confesses kneels before a priest, the confessor, and tells him that he committed a sin, that he wishes to reveal what he did and implore God to absolve his sins.

After hearing it, it is up to the priest to grant his words of suggestion, censure, guidance and comfort to the penitent, to recommend the penance to be consummated. The confessor must pray the prayer called the Act of Repentance, after the priest confers the words of absolution and blesses the penitent, who leaves to serve the sentence ordered.

The Catholic Church considers that the sacrament of penance is a purifying fact, which must be exercised prior to the Eucharist, so that it is obtained with a clean soul by the absolution of sins. But, it is also understood that this purifying effect is to reverence, being beneficial for the spirit on each occasion that it is practiced.

One of the most rigorous duties imposed on the priest by the Church is the secret of confession. The priest has the strict and full obligation not to reveal what he hears from the faithful in the confessional. The non-observance of this duty is estimated as one of the greatest and most serious sins that a priest can incur and exposes him to severe penalties from the Church. (Jn 20,23; Jas 5,15)

Anointing of the Sick

Thanks to the sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick (previously known as Extreme Unction), the Church helps its children, who are beginning to be at risk of dying from severe illness or old age. The sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick grants the Christian grace to overcome the inconveniences related to the condition of serious illness or old age.

The Anointing of those who are sick is the sacrament by which the priest prays and anoints those who suffer to prompt healing through faith, hears their lamentations and promotes divine forgiveness. This sacrament can be granted to any person who is sick, and not only to those who are in a state of death at any moment. (James 5, 14-15)

holy order

The sacrament of Holy Orders is the one through which the mission entrusted by Christ to his Apostles continues to be practiced in the Church for all eternity. For the social requirements of the Church and the civil community, Jesus Christ established the Priestly Order and Marriage, ordered for the redemption of others; that is why they are known as sacraments at the service of the collective.

The sacrament of Holy Orders grants the power to perform ecclesiastical occupations and ministries that are concerned with divine worship and the redemption of souls. It is separated into three levels:

- The Episcopate : It grants the totality of the order and makes the candidate legitimate heir of the apostles and the offices of instructing, sanctifying and directing are entrusted to him.

- The Presbyterate: Conforms the candidate to Christ the priest and benevolent shepherd. He has the power to act on behalf of the head Christ and provide divine worship.

- The Diaconate: Gives the candidate the mandate for service in the Church, through the worship of God, the sermon, the guide and above all charity.

Marriage

The marriage union between man and woman, created and shaped by particular laws granted by the Creator, is mandated by its very nature to the communion and well-being of the spouses, and to the conception and formation of children. Jesus has taught us that, according to God’s initial purpose, the covenant of marriage is inseparable: “What God has joined together, let no man divide” (Mk 10, 9).

It is the sacrament that constitutes and blesses the alliance between a man and a woman, and creates a new Christian family. Marriage is the union between man and woman, officiated in the Church and sanctified in durability and loyalty.

A distinctive characteristic of the sacrament of marriage is that it is not celebrated by the priest, but by the same couple who, performing the sacrament before the Church, pray and obtain from the priest the blessing for the new family that is born in that act.

The Orthodox Churches also commemorate these seven sacraments. For the Reformed churches, as alluded to above, such signs express grace, but do not bestow it.

Hello! Let me enthusiastically introduce myself as a dedicated blogger fueled by an intense passion for meticulously crafting insightful and well-researched blogs. My mission revolves around providing you, dear readers, with a veritable treasure trove of invaluable information.